網絡盜賊冒充你的身份及偷取金錢?

Is the digital double posing as you stealing your cash?

BBC News Technology 2015-09-30 11:00:00http://www.bbc.com/news/technology-33639440

When we go online to tweet, post, like, email or chat we surrender small pieces of our identity as we do so - a surname here, a nickname there, the name of our favourite pet.

These tidbits of data seem harmless by themselves because they are spread thinly across many different places. It would be impossible to tie them together and turn them against you, wouldn't it?

No. Not at all.

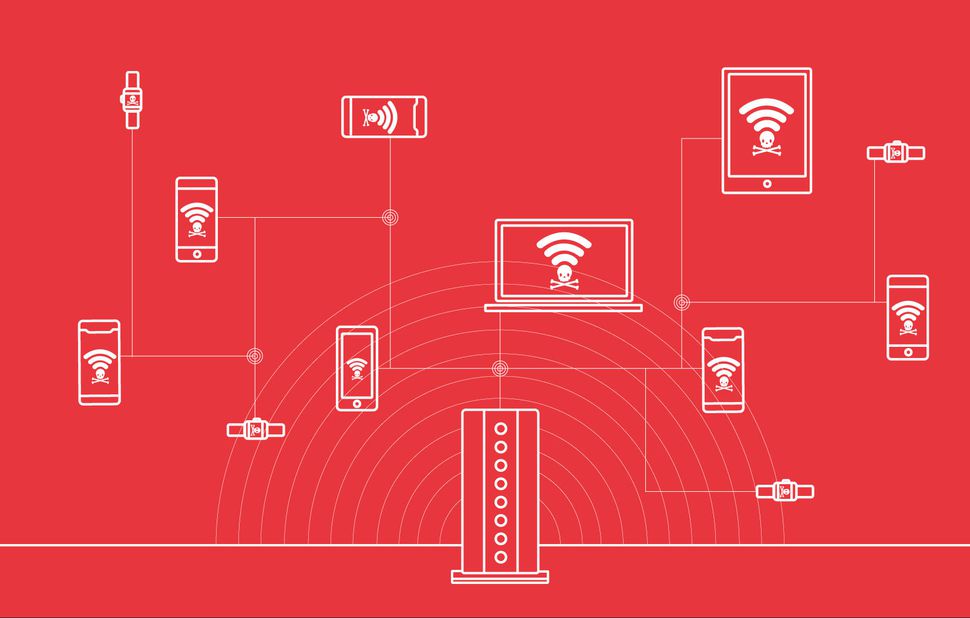

Cyber-thieves are getting very good at compiling all these pieces of you and adding to them to other stolen data to create a shadowy whole, a digital double or doppelganger; a phantom copy of you living in cyberspace.

They can then use these phantom identities to steal your cash, buy things, and apply for loans, mortgages and state benefits.

The fullz monty

These thieves and fraudsters have a growing appetite for what are known as "fullz", says Ryan Wilk, a director at security firm NuData Security, which has studied how those pieces of personal data are bought and sold.

As the name implies, fullz are complete data profiles of potential victims.

"They take chunks of data about a person and see how it can better be substantiated so they can add more value to it," he says.

A fullz profile might include your:

- social security number

- name and address

- date of birth

- phone number

- credit card number

- local bank branch name and sort code

- bank account number

- social media likes and dislikes

The more complete the profile the higher the price it can fetch on the black market. A stolen credit card number, for example, will sell for a dollar or so, but a fullz will go for $27-$100 (£17-£64).

"Credit cards are very valuable on day zero, but as the days go by the value goes down quickly," says Mr Wilk.

By contrast, fullz have a longer shelf life and give fraudsters more places where the information can be used and abused.

Data glut

NuData estimates that more than 675 million data records have gone astray in the US in the last 10 years, either because hackers have managed to bypass companies' security systems and raid their databases, or simply because a company has mislaid them.

"Breaches are just one part of the whole supply chain," says Mr Wilk.

They give the bad guys a massive pool of data to trawl through when compiling those fullz. They look for overlaps between data from different breaches to see if someone uses the same login name, password or other identifier on different sites and services.

Sometimes, he says, websites and companies inadvertently help this sifting process because of the way their online login systems work.

Many respond to a failed login attempt with an error message that reveals if a valid email address or name was used. Many cyber-thieves use these as a first stop filtering system to weed out the bogus addresses as they compile their fullz.

Leaky systems

"There's a lot of data that is out there by accident," says Alastair Paterson from security firm Digital Shadows.

"I'm always surprised by how much just leaks out in various ways with people not meaning to expose it or share it."

Some of these leaks come about via home workers accidentally exposing home data stores to the web and businesses using cloud-based document-sharing systems, he says.

Looking through those can secure all kinds of useful information about a company, its employees and how they structure data - all useful for any cyber-thief drawing up a dossier on a target.

Sometimes, says Mr Paterson, the leak is not the fault of the company that gets hit with a data breach.

One bank that Digital Shadows works with has more than 17,000 suppliers, he says, making data security even harder.

"Even if [the bank is] bullet-proof they are sharing a lot of information with that big supply chain and some of that will just get out," he adds.

Tracking the data

So where does all this stolen and lost data end up?

To find out, security firm BitGlass digitally watermarked a tranche of fake data that outwardly resembled the real deal.

It included a spreadsheet of 1,568 fake employee credentials, including social security numbers, addresses and credit card numbers, and was made to resemble the data stolen from health insurer Anthem.

BitGlass then posted the data on a few of the places cyber-thieves are known to hang out on the "dark web" to see if anyone took the bait.

They did. Within 12 days the data had been shared with people in 22 countries, was viewed more than 1,100 times, and the spreadsheet was downloaded 50 times.

Rich Campagna, a spokesman for BitGlass, says analysis of what was done with the data revealed that separate gangs in Russia and Nigeria were the most active in examining the contents.

"We saw eight-10 people in each country that were passing around the files," he says. "Primarily they were discussing it and trying to validate it."

Those efforts failed because the data was not real but, says Mr Campagna, it was indicative of the lengths criminals will go to in order to ensure the data they get hold of is useful or saleable.

Dodgy behaviour

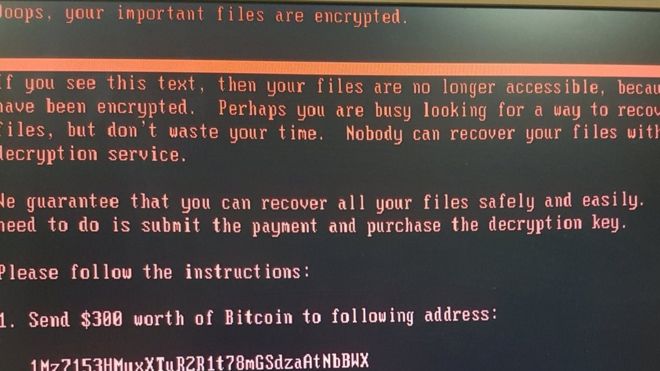

Once they've compiled useable fullz profiles, thieves need to test that they work.

"We typically see three or four test logins for every fraudulent purchase made via that account," says NuData's Mr Wilk. "That's where you see the bad guys validating the data."

The first login will probably be automated to ensure the account is live, and the second will be by a human to see what access it grants.

"But it's the third or fourth login that is the time they go in and place the fraudulent purchase," he says.

The good news is that the pattern of those login attempts can be spotted, so many companies now log behavioural data so they can spot dodgy activity when it happens.

How someone types in a password, clicks a mouse, and navigates through a website adds up to a behavioural signature.

This, at least, will be something fraudsters find almost impossible to copy.